Napoli

Naples 1982-1983 (1)

I first went to Naples for three months in the spring of 1982. I was 23, and this was my second year as a graduate student. It was the Biblioteca Nazionale that drew me there—more precisely, the unique collection of papyrus rolls that was discovered by accident in the middle of the 18th century in the ruins of ancient Herculaneum and that—after several moves, including one in 1805 to Palermo to keep them out of Napoleon’s greedy hands—is now housed there. I’ll talk about them in another post. This is more about Naples as a city and what it was like for me then.

OK. What it was like for me then was like landing on another planet where you don’t speak the language and you find the air hard to breathe. Where there don’t seem to be any rules, except really obscure ones that you don’t know you’ve broken until someone tells you, pitying your ignorance. Where no-one even notices traffic lights (where they exist, which is rare), let alone observes them. Where “No Stopping” and “One Way” signs are purely for decorative purposes and speed limits a joke. Where smoking isn’t allowed on buses, but people smoke in the Library, in lifts, in churches, and even in hospitals. Where it’s impossible to buy pure fruit juice or plain yoghurt or muesli, but fresh fruit and vegetables are astonishingly cheap and delicious. Where all the shops close on Saturday afternoons so everyone can go to the beach (these are still the summer opening hours for many stores; in winter they stay open on Saturdays and close on Monday mornings instead). Where churches (I had never seen so many churches!) have a Mass early on Saturday evenings so that—you’ve guessed it—everyone can go to the beach on Sunday. I was brought up Catholic and for me this phenomenon came to sum up Naples, and maybe Italy too. ‘Yes’, the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church says, ‘You have to go to Mass on Sundays, only we’ll pretend Saturday is Sunday and everyone will be happy. We’re sure God won’t mind.’ If God is Italian, I expect He doesn’t. He probably goes to the beach on Sundays Himself.

This is also a world in which there are no cash machines. If you want money you have to go to a bank and wait in the line (if there is one: usually there’s a scrum and then one of those invisible rules is applied to select the winner) for a bored clerk to fill in lots of unnecessary forms and apply stamps to them in about fourteen places. (There’ll be another story about one bank in particular later. I am looking at you, Banca Commerciale d’Italia.) It’s a world where young people of my age are attending university yet still living at home with their parents, with no place to make out—except for the long row of cars that begins parking up on Via Posillipo around 7pm on Saturday evenings, newspaper plastered over the windows on the inside, which are usually so steamed up you can’t see anything anyway. I had in effect been living away from home since I was 17, and I think the friends I made found me enviable and rather sad at the same time. Which, all things considered, I was.

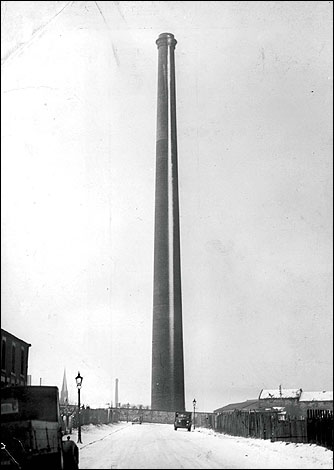

It’s also a dirty, rubbish-strewn, uncared for world—though people’s houses are spotless—and washing is hung out in the streets to dry in the often filthy air. The women who live in the bassi, tiny homes before there were such things, squeezed into the façades of older palazzi next to the large entrance-gates, have it worst. Unless they’re lucky enough to have an upper floor crammed into the same space, with a tiny balcony uptop, washing has to be arranged on stende right out in the street, with cars and motorini zipping by no more than a foot or two away. Life must be one long cycle of cleaning and washing for these housewives. And all around rubbish accumulates at terrifying speed, especially near the many small street-markets. Every night the dustbin men, as I once called them, or garbage trucks, as I call them now, come round to collect the munnezza (Neapolitan for immondizia), and I came to think of them as King Canute, trying ever and again to stem the rising tide of refuse. They still are. At least the towering chimney in eastern Naples rising out of the facility that once burned some of the rubbish no longer spews God knows what into the air. It made me think of of the giant 312’ chimney known as the “Audley Destructor” which towered over my home town between 1888, when it was built (the year of Jack the Ripper) and 1959, when it was demolished, and which also belched incinerated refuse into air already thick with smoke and soot from coal fires and factory chimneys. At the time it was the tallest chimney in the UK.

Naples, and indeed the whole of Italy, is still working out what to do with it all that munnezza. The camorra doesn’t like the new termovalorizzatori (waste-to-energy plants) because it doesn’t control them, and there are reports of sabotage and of orchestrated strikes amongst garbage workers. Organized crime is also happy to make money off the wealthier north of Italy by importing refuse from Milan and Turin and dumping it illegally in disused mines and quarries around Naples, or just spreading it on fields right next to growing crops. The worst stuff percolates into the ground water. Not so many years ago an entire tanker-lorry full of toxic waste was discovered buried in what is now called the “Triangle of Death” for its abnormally high rate of cancers, especially in children, and of pulmonary and coronary disease.

And yet you can see this sort of thing (photos taken in January 2015, but the scene hasn’t changed much in the intervening 36 years). A storm is moving from north to south across the Bay; on the left of the second picture, Capri is completely hidden from view by the dense but shifting cloud.

A nice pair of knockers 1

That title is designed solely to draw people to this site. What you’ll find is this: a selection of photos of some of the wonderful doorways I found in Naples and Sorrento on our last trip to Italy in 2018-2019.

Part 2: London Knockers.

Naples: street shrines

Wayside shrines are everywhere in Naples: on every street-corner, in the smallest alley and on the busiest piazza. I grew up Catholic, but England isn’t peppered with wayside shrines the way Italy is, let alone Naples. Many of these shrines are not well-maintained, however. The protective glass or plastic is often dirty, scratched, or cracked; the statues and crucifixes within may be dusty or broken; photos and ex votos placed inside may be sun-bleached, like the plastic flowers often arranged in vases or jars. This neglect isn’t recent; I remember it already back in the 1980s. But some people still take care of shrines, hard as it is in such a dusty, filthy city, and they cross themselves as they pass by. Religious processions for saints’ days and festivals are frequent, with young people in marching bands or carrying banners. We saw fresh flowers too, and recent offerings.

Recently we walked up via Salvatore Tommasi, where the Carabinieri have their regional HQ, but is otherwise an ordinary, not very prosperous residential street, and saw that ceramic plaques had been put up commemorating the appearance of the Virgin Mary to St Bernadette at Lourdes. Here are the ones we found, starting from the eastern end of the street.

In the first is set out the second and third speeches by the Virgin to Bernadette: she asked her to come here for 15 days, and promised to make her happy not in this world, but the next.

‘Are you willing to come here for a fortnight? I promise to make you happy, not in this world, but in the other.’

‘I want people to come here from every part of the world…‘

‘Pray for sinners.’

‘Repentance, repentance, repentance.’

[Well, not here, obviously.]

‘I want people to come here in procession.’

Apparently the next words were said during the ninth apparition of the Virgin:

‘Go to the spring and drink, and wash yourself.’

I think the next words refer to the bitter herbs the Virgin told Bernadette to eat as a sign of repentance and suffering, rather than to the Eucharist:

‘Take and eat.’

We also walked down part of one street, via Francesco Saverio Correra, and these are the shrines we saw on the way.

At this point we saw a war memorial, which I thought I’d include for its historical interest:

Fante means infantryman; ‘Mar.’ stands for marinaio, sailor; Geniere means he belonged to the equivalent of the “sappers”, the military engineers; ‘Av.’ is short for ‘Aviatore’, that is, airman, and ‘Art.’ for ‘artigliere’, artilleryman or gunner.

Note that in Italy WWI ran from 1915 to 1918, and WW2 from 1940 to 1943. In September of that year Italy went over to the Allies, and immediately found itself with a hostile occupying force on its hands. The memorial we found nearby on another street has to be understood in that context:

This Memorial is different. It does list two sailors and a soldier who fell in the War, but more striking is the list of people who are obviously civilians: three from one family, three from another, a child (little Pasquale Marino) and one other person, ‘all made brothers and sisters by the holiness of sacrifice’.

So many civilians could have been killed only during the “Four Days of Naples”, Le quattre giornate di Napoli, when the Germans, the Nazifascisti, were being chased from the city—perhaps, some say, unnecessarily, as they were already leaving of their own accord. I found a web-page that lists them all (or all but one) as victims of the random cannon-fire from the big gun placed by the German commander, Colonel Walter Scholl, in the Castel Sant’ Elmo on top of the hill overlooking the city, which was allowed to fire at random at any target. As a result the Reale family lost a man, perhaps father of the two sisters. Annamaria Finale was only two; Salvatore may have been her father; Francesca, née Dorso, her mother. The Finale family lived at no 18 Vico Bagnara, the Reale family at no. 12, and no. 16 was also hit, perhaps by the big gun, perhaps by machine-gun fire, and someone else died there—Giuseppa D’Ambrosio according to the memorial, Giuseppe according to the website, which doesn’t mention little Pasquale.

The Quattro Giornate are a controversial topic, and I won’t go into it here. But this memorial is a reminder of how good it is to live in a country that hasn’t been invaded since 1066. Or hasn’t had a civil war since the 13th c. (looking at you, Switzerland).

Padre Pio, in case you’ve never heard of him, is everywhere in Italy. (My husband and I refer to him as ‘Padre Prezzemolo’, ‘Father Parsley’, because Italians say of something ubiquitous that it is ‘come prezzemolo’, ‘like parsley’.) He was a priest and Franciscan friar, who lived a life of great holiness and self-denial. He reputedly suffered the stigmata on many occasions, beginning in 1918, and claims were made that he had other supernatural gifts associated with saints, such as bilocation. Interestingly, Pope John XXIII (like several other Popes) was not convinced by Padre Pio, and in 2007 it was revealed he had been kept secretly informed of Pio’s activities, especially with regard to the women who formed an almost unbreakable circle of protection around him. Nonetheless, he was made a saint in 2002 by Pope John Paul II (“Pope Ringo” to readers of Private Eye, as in ‘John, Paul, George, and…’).

The underlying conflict may be between two ever-present currents in the Roman Catholic church, one—which tends to be especially strong amongst the less educated—towards mysticism and miracles; the other towards doctrine and the authority of the Church hierarchy, which may either exploit or be threatened by the populist fervour of the other current, especially when major changes are under way, as with the Second Lateran Council. Padre Pio lived in Italy for the duration of the Fascist regime, and seems not to have had one bad word to say about it, not even about the racial laws.

(Apologies for quality of this image, but I wanted to show it anyway.)

your name creates harmony, murmuring Ave Maria.‘

There follows a list of the men who put up or restored the shrine. The lower inscription says: ‘Passing by this cross, you will make the sign of the Holy Cross, and then ask the Lord to save your soul.’ And people doing just that are still a common sight in Naples.

Naples: degrado

I have to confess that Naples depressed me more on my last visit (2018-2019) and more and more as time went on. It seems more squalid, less cared for, and perhaps a bit less friendly than I remember. It was certainly squalid when I came in 1982, when the Piazza del Plebiscito was one huge car park, pedestrian zones were unheard of, buses trundled all the way down via Toledo to Piazza Trieste e Trento and struggled to turn left onto the street in front of the San Carlo. It was a much more provincial city then; there were few foreigners (on buses, people would form a half-circle and simply stare at me); but, at the same time, the Neapolitan dialect was something to be hidden—it was not part of a glorious heritage stretching back hundreds of years, but a tatty and above all working-class remnant of Spanish subjugation, best forgotten in favour of the language of Petrarch and Dante.

(The Church itself is beautiful inside, and well worth a visit.)

Today Naples seems meaner now, more “degraded”, than it did then, perhaps precisely because the contrast with the ideals of a “normal” city has been made more vivid by the many improvements. Yes, there are pedestrian zones… but motorini still zip across them at break-neck speed (your neck, not theirs), especially coming out of or going into the Quartieri. People do on the whole carry out the differenziata, the separation of paper, plastics, metals, and glass for recycling… but the recycling industry is in the hands of the camorra. Moreover, heaps of rubbish appear almost everywhere you go. There are innumerable splendid buildings in Naples, churches and chapels, libraries, universities, private palazzi… but the neglect of them is deeply saddening, and a bit worrying, as with the fall of chunks of cornice from the Galleria Umberto (recently repaired) and of bits of cornice and plaster from many other buildings around the city (everywhere netting is attached to buildings to catch these missiles before they hit an unsuspecting passer-by). And there are more serious problems too. Here’s just one example.

Recently the 16th-century Ospedale di Santa Maria del Popolo degli Incurabili had to be closed in a hurry because of concerns about its safety. Legend has it that the sea-nymph Parthenope, who gave her name to the original settlement that would one day become Naples, is buried under the hill on which it stands; unfortunately, this hospital complex, which originally had male and female wards for syphilitics, the insane, and the dying, as well as a (male) military ward and a ward for pregnant women, and which has five (I think) churches and a stunning 18th-century pharmacy, is slowing sinking down to join her. There had been warning cracks in floors, and part of the pavement behind a main altar in one of the churches had already given way, threatening the resting-place of the hospital’s foundress. In April 2019 the whole complex was cleared of patients and staff. I fear it will now stand desolate and empty for decades—except, probably, for illegal immigrants and other homeless people with nowhere else to go.

There are also several museums of art with important collections and exhibitions dotted around the centre of the city… but the rest of the city seems to be covered, up to the height of 7 or 8 feet, with graffiti at once lurid, threatening, and banal. There are some who consider graffiti, or at any rate some graffiti, art, and it’s true Banksy became a draughtsman at some point before he adopted his fashionably working-class nom de guerre. It’s true, too, that here and there, especially in the University district of the centro storico, the graffiti are far more imaginative, with a fine sense of how colours work on each other, although shading and perspective are non-existent, as no-one knows how to actually draw. But the rest is just gang symbols, names and initials, and professions of love, plus, of course, pornography, which, whether written or figured, unites the intensity of adolescence with all of its subtlety.

I do not know why some people have the patience to stand on a box for however long it takes to draw or write this stuff, and maybe others burst into song spontaneously on seeing the results. But it seems to me that if the graffitisti stood on a box and shouted—at the tops of their voices, for hours at a time, in front of small children and old ladies—their names, their tags, their political views, their sexual achievements and desires, or their ownership of some few square metres of squalid housing and unhealthy backstreets, then even Neapolitans would sooner rather than later deck them or at any rate put them in a straightjacket. Or else they’d have to be rescued by the police from a lynch-mob. Given, however, that they constantly invade, not our aural space, but our visual one, with lurid characters several feet high, everybody seems just fine with it. Why?

The exasperation of citizens in face of the degrado of the city is evident in this sign:

And when I say central Naples is full of graffiti, I mean it is full of graffiti. Every surface of every public building, save police stations and carabinieri barracks, has that solid band well over two metres high; even the rusticated stone of the most prestigious institutions isn’t spared. The same is true of most private palazzi if the aren’t cut off from the street by walls and gardens. The steel gates and shutters that protect every shop after hours (many with no distinguishing marks, presumably so you won’t know if you’re breaking into a jeweller’s or a coffee-shop) are covered with it; so are street lights, bollards, traffic signs. You name it, it’s covered in graffiti. No-one tries any more. The Central Post Office on Piazza Matteotti, a magnificent building even if the Fascists did put it up (1928-36), has been trashed by a combination of graffiti, the rubbish left by careless, indifferent slobs, and homeless people sleeping in the alcoves—a wonderful original feature by the architects Vaccaro and Franzi—along via Monteoliveto. The other Fascist-era buildings nearby, built when one of the worst slums was done away with, and which in any other city would be treasures, cooed over by lovers of modernism, are adorned with weeds, broken windows, and, of course, graffiti.

Or take this wonderful building, the Galleria Principe di Napoli.

Being so close to the Archaeological Museum (the “MAN” as it’s now fashionably called), it ought to be full of cafés and shops selling souvenirs, jewellery, and books to tourists. Instead, it houses offices of the Comune, plus a few artists’ and designers’ workshops, and fashion shows are held there every so often (or were, anyway).

It has an interesting history, showing how difficult change has been in Naples. It was built as part of the massive changes to this area after the demolition of the state grain depositories dating from the late 16th and early 17th centuries (they were called the “Fosse”, literally “ditches”, from their origin as natural cavities in the ground, although the later versions, which I believe stood more or less where the Galleria stands now, was just a normal warehouse). Via Toledo was extended towards the then new Museum, along what would eventually become via Pessara. Via Bellini was constructed too, while one of the gates in the City wall, the Porta di Costantinopoli, was demolished. But actually creating something new out of the area seemed to be beyond the power of the city. A portico was built along via Pessara, or whatever it was called then, and eventually—very eventually—there came to be a real galleria, or “mall” as the Americans call them. Building it took almost 15 years, on and (mostly) off, between 1869 and 1883. The architects were Nicola Breglia and Giovanni De Novellis, and they must be congratulated for their tenacity as well as for the gracefulness of their design, with its wrought-iron and glass roof, and the clever way in which the building was adapted to the rising ground here.

The Galleria survived World War Two, but almost a hundred years after its inception the north frontage, which also has a portico, collapsed all by itself in 1965. Fortunately, plans to replace it with some dreary 1960s sub-modernist block of offices and flats were foiled, and the frontage was replaced. It then became basically an indoor football field for local youth, who systematically took it apart, breaking everything that could be broken. So it was closed again. Finally, in 2007, a full restauro began, and I saw it soon afterwards. Sadly, as I said, it is not usuallly open to the public now, and it looks derelict and mournful; the facade towards via Pessara has turned into an informal dosshouse for the homeless. Its wonderful location for exploiting the tourists who come to the Museum is of no interest to the powers that be, although, apparently, yet more restoration work is underway. At any rate there are the usual bits of scaffolding and those metal structures that look as if they are closing off a work-in-progress area, but that instead hang around for years while nothing happens. I expect the ghosts of Breglia and De Novellis, are, somewhere or other, doing face palms.

Finally, another example, from the Piazza del Mercato down near the Port, which at the time of our visit was basically a huge open-air bomb-site. I hope the pandemic hasn’t stopped the restoration of this area. These sphinxes made the walk there worthwhile, though.

Naples: introduction and bassi

I’ve been coming to Naples, on and off, since 1982. I’m neither an ex-pat nor a local (I’m not even Italian), and I have never lived here for more than ten months together. But I’ve lived in different parts of the city, and I have seen Naples change so much; so I think—I hope—this may give me a unique perspective. In a way, I have seen, not one, but several different cities.

There are still many, so very many things I do not understand about Naples. Not speaking Neapolitan is a real drawback. (Incidentally, a friend of ours recently visited Barcelona, and found he could understand Catalan perfectly. That’s how little has changed in four hundred years.) So the point of this blog is, really, to try to get some explanations, from people who know more about Naples, of certain sights and sounds and experiences that have left us baffled. Some of them concern Italy generally; but most are strictly Neapolitan. If you have answers, please, pass them on. Thank you in advance.

Santa Maria Regini Coeli Church